Made in Space: Paintings from 1992 - 2001: Herbert Creecy

Johnson Lowe Gallery is pleased to present Made in Space: Paintings from 1992 -2001, a solo exhibition of never-before-exhibited works by Herbert Creecy. On view from February 21, 2025 – April 19, 2025, the exhibition highlights a selection of paintings from 1992–1997, a period in which Creecy pushed his process into new conceptual and material territory. Made in Space offers a rare look at the artist’s late explorations with polyurethane transfers and air compressors, revealing a body of work where spatial fragmentation, levitation, and architectural form converge.

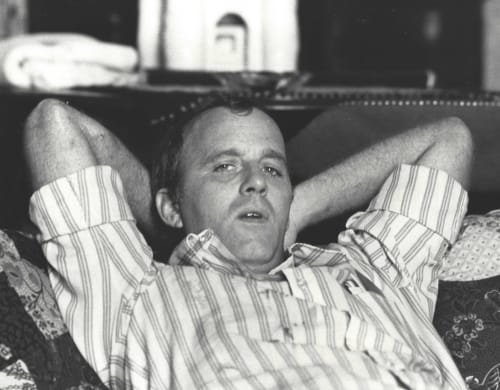

For half a century, Herbert Creecy worked at the edges of recognition, a prolific and restless painter who stayed in the South while the center of critical discourse remained elsewhere. His canvases—layered, scraped, collaged, and often monumental in scale—were never fixed things. They were built up, broken down, and reassembled in a process that felt equal parts instinct and strategy. If his early works, with their fingerpaint-like squiggles, were collected by the Whitney, the Corcoran, and the High Museum, it was because they slotted neatly into the wider history of American postwar abstraction. But Creecy was never interested in slotting in. From the Shakin’ Shanties of the ’80s to the cannibalistic, self-consuming collages of the ’90s, each series fed off the last, absorbing and repurposing past gestures until the work, and the artist, collapsed under the weight of constant reinvention. He produced over 3000 paintings, but for all their ambition, they remained largely underexamined. The research simply never caught up to the work.

Made in Space presents a different side of Creecy. The paintings here, most never before exhibited, date from 1992 to 1997, a period when he stripped his process to its bones. Space, form, and the tension between impulse and structure became the focus. Paint wasn’t just pushed and pulled anymore; it was transferred, compressed, displaced. Polyurethane lifts and air compressor bursts replaced the brush. These work took on a new kind of precision.

Some paintings, like Untitled, Black and Purple Composition (1995) and Untitled Red and Green Composition (1997), feel almost architectural—latticed tendrils, skeletal scaffolds, and fragmented geometries tangled together like structures in mid-construction or collapse. There’s a sense of engineering at play. Creecy had a lifelong fascination with aeronautics, building model planes and sketching them into his work, and here, that interest in levitation and trajectory is unmistakable. Forms hover, intersect, and suspend themselves in ways that feel less like paintings than diagrams of unseen forces. Others, like Concubine (1992) and Judith’s Pond (1989–1997), move in a different direction, away from structure and into atmosphere. Pigment accumulates like sediment, dissolves into liquid depth, drifts into planetary suspension. If the earlier works feel engineered, these feel eroded, their forms shifting between micro and macro, geologic and cosmic, cellular and celestial.

Creecy never quite abandoned Abstract Expressionism, but by this point, he had retooled it. These paintings weren’t just responding to their own internal logic—they were in conversation with the ideas of their time. The tension between modernist faith in materiality and postmodern skepticism toward gesture and authorship is embedded here. Creecy, for all his embrace of improvisation, was always aware of where his work stood in relation to both histories. And these paintings move between them. They don’t just exist in space—they map it, construct it, erode it. Across them, Creecy doesn’t simply compose; he builds, excavates, displaces. And in the end, the work hovers, just as it always has, between fact and fiction, between the terrestrial and the aerial, between gesture and the ghost of a gesture.